There are lots of issues which the new Labour Government needs to grapple with in education. Bridget and her team will have been handed a number of tricky policy knots: the teacher pay deal, RAAC crumbly concrete and a system currently ill equipped and funded to support children with SEND, to name a few.

Whilst these issues are all obviously important, there is also a medium-term commitment – the curriculum review. So, in this piece I ask – where are some areas where the Government can make genuine progress? I look at how they could make some quick progress in a no or low-cost way given the current fiscal constraints, and where tougher decisions will be further down the line if we truly want to build an education system that will last into the future.

You can be both “broad” and “in-depth”

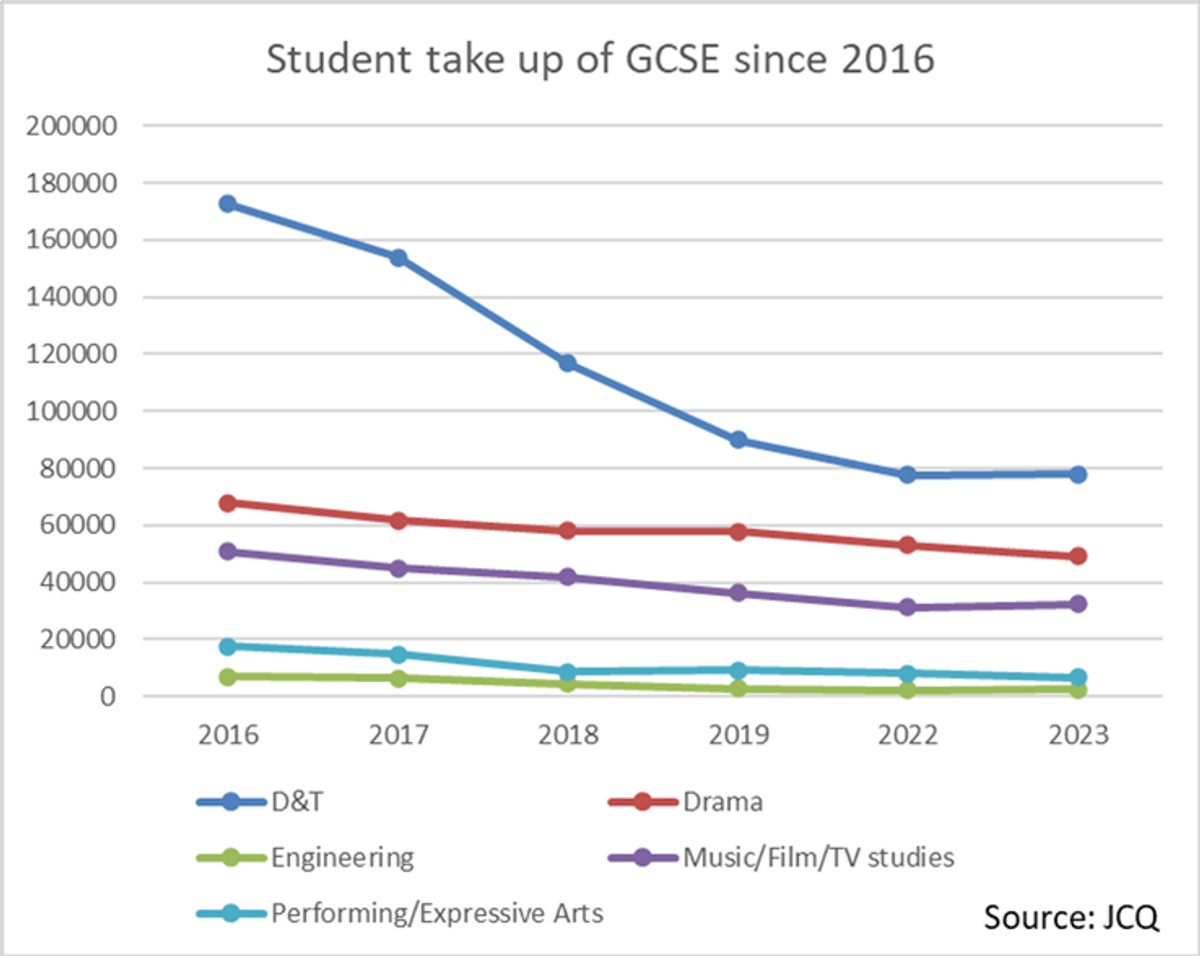

Current 14-16 education programmes have seen declines in creative and practical subjects taught. For example, entries to Design and Technology have plummeted 54% since 2016. This is partly a result of the EBacc suite of subjects focusing on traditional academic subjects, and partly it is down to the Progress 8 accountability measure. Whatever the causes, many subjects have declined dramatically.

For more details see: Examination results - JCQ Joint Council for Qualifications

For years, there has been debate in education circles about whether you should focus on a broad course of study encompassing many different subjects or go in-depth on only a few. The short answer is: you need both.

Increased breadth is a positive aim as a broad education develops a mixture of core skills and knowledge which ensure success outside the school or college gates. But it should not be at the expense of depth. We need to preserve the best bits of our system, like the internationally respected A-levels which provide the depth and rigour that universities appreciate.

Labour announced plans to update the Progress 8 accountability system to include creative and vocational subjects. These plans are broadly feasible and can be done with an administrative shuffle of the pack, rather than a wholesale redesign of the system – something which would appeal to an education workforce who have been crying out for stability. While everyone agrees you should have both, it is important that we all recognise that you can have both.

One way you can do this is through changing the means of assessment, while keeping a focus on core academic subjects and knowledge. End-point, high stakes summative exams are fantastic at what they do, but they are not the only method for measuring competence in a particular subject area. There are a whole host of different options open and available to measure what a candidate has mastered, which would provide a broad, balanced way of assessing young people’s knowledge and skills.

For example, project-based courses could increase breadth while preserving rigorous standards and depth of study. The Government could introduce project-based qualifications alongside GCSEs, which could be taken instead of an existing qualification. These could be modelled on the existing Higher Project Qualifications (HPQ), the Key Stage 4 equivalent of the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ). Project qualifications enable students to develop their own independent study and project skills in an area which interests them, and so should be a cornerstone of a broader education system based on a mixed framework of diverse types of assessment. The Government could also look at what role a presentation or viva-style assessment method could play, to encourage greater oracy development.

We can have a sensible debate on curriculum, without getting bogged down in culture wars

Heated curriculum debates and how we best prepare our young people for the world they will enter are nothing new – but they have become particularly loaded in recent years. Certain terms are deeply loaded with baggage which can be unhelpful, even when large swathes of people agree with the underlying sentiment. And what we can see is that message discipline is critical, as the wrong phrase or word can throw you into the trenches. Lisa Nandy, the new Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, seems to agree, promising that the “era of culture wars is over.”

For example if we take the phrase decolonising the curriculum, polling by Public First has shown that the extent to which people support changes depends on the language used. What the report found was that people were more likely to support changes to the curriculum if it was framed as a process of “broadening perspectives,” than when “decolonisation” was used.

At AQA we have a lot of experience in creating curricula that prepare students for modern Britain, and present students with the best that has been thought and saidby a whole host of authors, playwrights, designers, and thinkers. And when we do that, we use language that shows how those curriculum choices support a broadening of perspectives.

We are also working to embed critical, cross-cutting issues – such as climate change – across different subjects, to help students both build their interdisciplinary understanding and ability to grapple with thorny issues.

Government can make progress by creating the space for these evidence-led, sensible conversations, and steering us away from the divisive culture wars we have too often experienced in recent years.

We need to embrace the power of technology

Labour has said that “the teaching of digital skills and navigating online platforms is out of step with the reality of young people's lives,” something that at AQA we also identified in our report ‘Towards new assessments for Numeracy, Literacy and Digital Fluency.’

We believe that digital assessments have huge potential for measuring fundamental skills that all individuals need to develop to function effectively in society, work, and life. We need to embrace the power of technology to help us identify gaps in students’ knowledge, so that teachers can address them and prepare our young people for the wider world outside the school or college gate.

Other countries such as Estonia have worked through how these technologies can improve education. In Estonia, all pupils can work on iPads or classroom computers, using digital educational materials. All their learning materials are stored in the cloud meaning extensive progress data can be analysed and gaps can be identified for teachers to address.

We should follow in their footsteps and take a more digitally savvy approach to future education policy. We have yet to harness the potential that digital techniques have for improving assessment, from adaptive testing to gamified learning. The quick wins for a new Government would be to have efficient assessments which teachers could use to identify gaps in students’ knowledge, potentially helping alleviate pressures on workload around marking and assessments. AQA has experience in this area and have recently developed a new diagnostic assessment, AQA Stride.

Longer-term, there are tremendous benefits to a digital assessment system for high-stakes summative exams, which can assess a wider variety of skills and knowledge than traditional pen and paper exams. This longer-term work has a cost associated, of course, and any move to a more digital education system should not be rushed. But at the start of a new Parliament, a new Government has the opportunity to look up and ahead to what our education system could look like in the future and think about how we can best build a system to ensure we give young people the best possible start in an increasingly technological world.

With a new Government stepping into the corridors of power, and a new Education Secretary stepping into Sanctuary Buildings, there are a myriad of different issues to be grappled with. Once the dust has settled and the honeymoon glow subsided, we hope these three areas present a significant opportunity for meaningful change.